Decisions about whether to continue investing in a publicly funded program should be based on whether the program achieves its primary objectives, and its cost relative to effective alternatives. In practice, stakeholders often defend ineffective programs based on other considerations, like anecdotes about unplanned secondary benefits. If enough people get on that bandwagon, it’s easy to conflate popularity with positive policy outcomes.

Public policy problems tend to be complicated, with many contributing factors that make it hard to design programs that work well, and to reallocate resources away from programs that do not. Measuring outcomes can also be challenging. It’s often easier to evaluate the popularity of a program by counting participants or surveying opinions than to validate target outcomes.

Stakeholders motivated by a strong sense of mission may not have the skills to assess outcomes and opportunity cost. They may appeal to emotion or claim anecdotes about unplanned benefits as proof of value, even if the evidence for a program is weak. They may worry that ending weak programs is a slippery slope to withdrawing funding entirely, assuming that decisions are black-and-white, between this program or nothing.

Poorly targeted or ineffective programs not only fail to address the policy problems they are trying to solve, but also tie up scarce resources that could be invested in finding and delivering better solutions.

Consuming public funds and effort on programs that do not work, or that only address symptoms, locks us into a cycle of ongoing expenditure without addressing the causes of public policy problems. Even if programs have genuine unplanned benefits, the link between the investment and the outcomes is unclear, making it harder to assess the relative value of public spending. When funding follows stakeholder pressure, rather than outcomes, we reinforce a cycle of funding squeaky wheels, rather than vehicles for change.

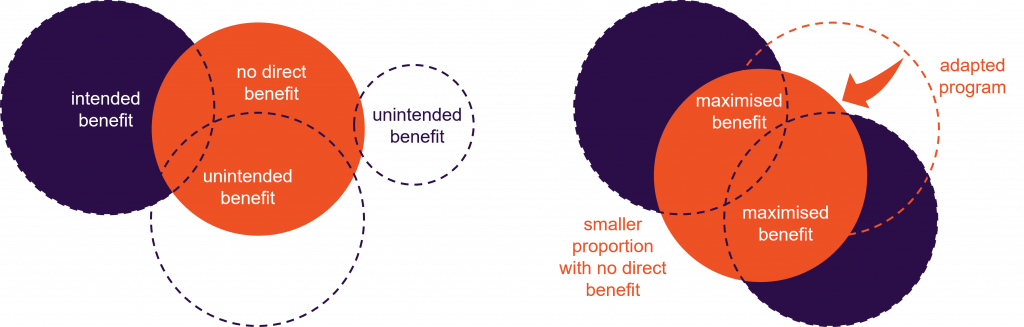

Collaboratively defining a program logic at the outset helps to clarify all the major goals of an investment for all the key stakeholders. This process also builds shared capability among stakeholders to contribute to, and understand, assessments of outcomes against those clear goals. By evaluating against an agreed program logic, we put the burden of proof on the program to demonstrate its ongoing value, rather on funders to defend decisions to withdraw resources or adapt ineffective programs. If we discover material unplanned benefits in the evaluation process, then we need to make a new business case and decide whether to re-invest scarce resources on that basis.

Tying funds to target outcomes instead of specific programs can help to allay fears of funding being lost forever if it is reallocated from a program that does not work, to a different way of meeting similar needs.

By clarifying what problems we are trying to solve at the outset, in collaboration with people experiencing those problems, we can adapt with greater speed and confidence if those problems are not being addressed.

Linking funds to outcomes rather than programs helps reduce aversion among advocates to perceived losses. When stakeholders know that funding is dedicated to a specific outcome, it is easier to support ending or adapting low-value programs as an opportunity to gain greater and more lasting value.

Building stakeholder capacity to assess the relative value of programs helps to ensure that reallocated resources find skilled delivery teams and supporters, rather than passionate opponents. Instead of vested interests defending weak programs with appeals to weak evidence, we need to build a stronger case for getting on the bandwagon to maximise public value.