Lobbyists are professional influencers, paid to persuade decision makers to act in favour of vested interests rather than for the broader public good. If there is not enough wider public interest in a policy question to offset the targeted influence of motivated individuals, decision makers can form a distorted view of the balance of interests. By advocating on behalf of paying private interests, lobbyists seek to tip the scales that we trust to be impartial.

Government decisions made on behalf of the public sometimes have significant consequences for specific individuals, groups, companies, or industries. Common examples include planning decisions about land use or decisions about heavily regulated industries like energy, gambling, or animal products.

Australia’s model of democracy is designed to ensure fair representation of the interests of constituents. This includes people and companies affected by government decisions.

Rather than represent themselves directly, some affected parties hire well-connected lobbyists to speak for them. Lobbyists can advocate more effectively than most other stakeholders, and generous donations help them to retain access to political decision makers.

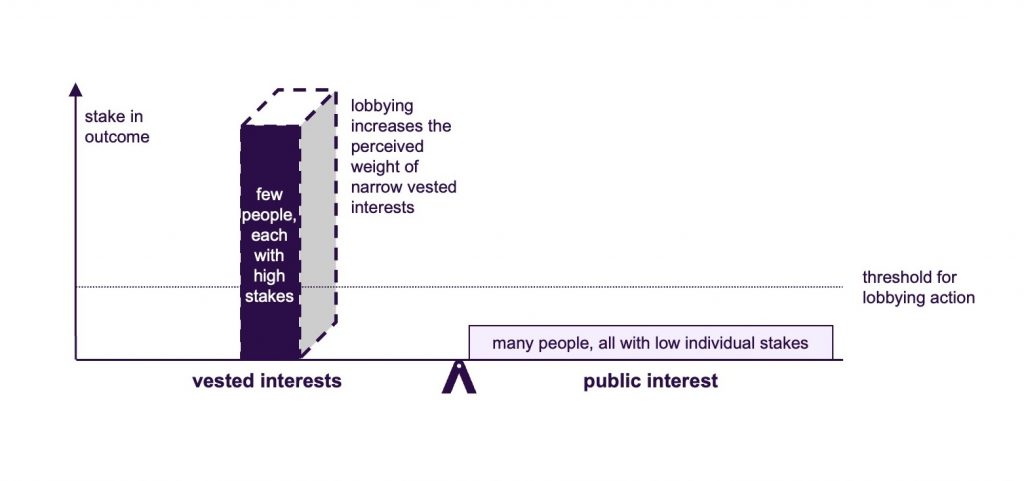

Lobbyists represent the interests of a few people, each with much at stake. They represent minority interests in a decision, such as nine individuals with $1m each at stake. The broader public interest can be larger, but more diffuse, such as a million people with only $10 each at stake. Small effects on a large group add up to large costs, but the effects on individuals are too small to trigger active engagement in the decision.

Lobbying on behalf of a few motivated individuals can disturb the balance of considerations perceived by decision makers. On one side are professional and articulate lobbyists, on the other side are less invested citizens who may not even be aware of the issue. Decisions that tend to reinforce entrenched advantages of the few at the expense of the many can damage public trust in government.

Most people want public decisions to balance public and private interests fairly. When public decision-making processes work well, without distortion, they are more likely to produce fair results.

Typical mechanisms to protect against lobbyists’ influence focus on transparency, such as listing lobbyists on a public register, requiring adherence to a code of conduct, and disclosure of lobbying activities.

Requiring decision makers to publish their reasons, including how evidence from various sources has been weighted, can encourage greater fairness. If lobbyists need to meet higher evidentiary standards to compete with public officials, debate can be informed by evidence-based estimates of costs and benefits for both vested interests and diffuse stakeholders.

Lobbying evolved to meet the needs of affluent people who are significantly affected by government decisions, but who lack the time or skills to advocate in their own interests. Over time, it has evolved into an industry of backroom operators peddling influence to subvert fair decisions.

Typical controls on lobbyists emphasise transparency about who is a lobbyist and what activities they engage in, but this offers little protection for the integrity of decision-making processes. We need transparency about what evidence informs public decisions and how that evidence is weighted, not just visibility of whether a lobbyist is engaged. Fairness in public decision making, and trust in public decisions, requires that we have fair scales, not just fair warning that a lobbyist might have a thumb on those scales.