People who work in publicly funded organisations are influenced by their personal and professional interests, as well as the public interest. People tend to prefer actions that are consistent with their personal goals and values, even if those actions are not the best way to maximise public good. These subtle influences on decisions and actions are often not recognised as a conflict between the interests of the worker and the interests of the public.

People and organisations tend to notice and respond to the things that matter most to them. Even with the best intentions, existing preferences and expectations make it easier to identify and choose some actions over others, and people who see themselves as highly committed to public value tend to assume that their preferences are aligned with optimal public value.

There is often no objective anchor for how to maximise public value. The evidence for any specific response, or mix of responses, is often not strong. Or there may be weak evidence supporting many possible answers. Individual or organisational preferences can even overpower formal guidelines, especially if workers are suspicious of the motives of the authorising environment or consider it to be uncaring.

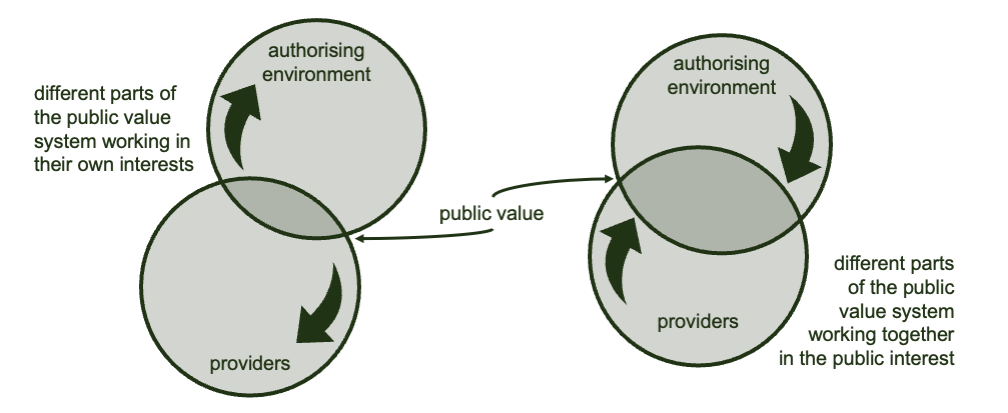

Individuals or organisations following their preferences in an uncoordinated way can lead to gaps and overlaps in service systems, especially when many people prefer to make the same sorts of contributions. Many more people are willing to raise money for rare childhood cancers, for example, compared with less sympathetic cancers that may be more common.

Leaning too heavily on individual preferences can also lead to relatively low value work being done by providers who enjoy it more, or find it more convenient, than higher value alternatives. Potentially valuable activity could also end up fragmented across many providers at too small a scale to be efficient. In extreme cases, provider preferences could even inadvertently harm the people they are trying to help.

The right to make decisions about the system, like how resources are allocated to different services or how authority is distributed, should be allocated to people who can see the bigger picture. Checks and balances, like formal funding agreements, procedural guidelines, and oversight mechanisms, help to define limits on the extent to which public resources can be directed by personal preferences.

Individual providers should respect the legitimacy of the authorising environment to specify its requirements and strive to meet those requirements in good faith. If experience on the ground suggests the need for a change, they should work with the authorising environment to renegotiate, not just divert public funds to do whatever seems best to them.

The preferences, opinions, and instincts of people working in publicly funded organisations have an important role in shaping public policy action. But, if given free rein, individual preferences can distort public action in ways that are inefficient, inconsistent, irrelevant, or even harmful.

Public value is created at many levels: at the individual level in interactions between workers and customers, and at the system level in the interactions of many different activities and providers. People who are well placed to make decisions at each level should be responsible for making the best decisions they can, and those decisions should be respected by people at all the other levels. Public value is not about doing what workers find most interesting, but working together to do what is most in the public interest.

social cohesion vs diversity