Publicly funded organisations strive to do complex work efficiently. They often break long, complex processes into sequential production lines where everyone works on one piece of the puzzle at a time, with little visibility of the final product or the other steps in the process. Mistaking an individual task for ‘the work’, it is easy for workers to think the work is done when they are, and rare for either the process or the final product to be done well.

Complex publicly funded organisations try to maximise efficiency by breaking work into a series of tasks, so each worker can focus on one part of the process. Sometimes coordination is assigned as a separate task to one or more people. Serial individual contributions are consistent with how most people were trained: working largely alone through cycles of rework with periodic feedback, rather than in teams where everyone can see the overall goal, each step, and the interactions between them.

Enabling individuals to focus on just one step in a long and complex process can be efficient. It reduces distractions and the effort required for each worker to understand the context, maintain visibility of other steps, or attempt to influence other steps.

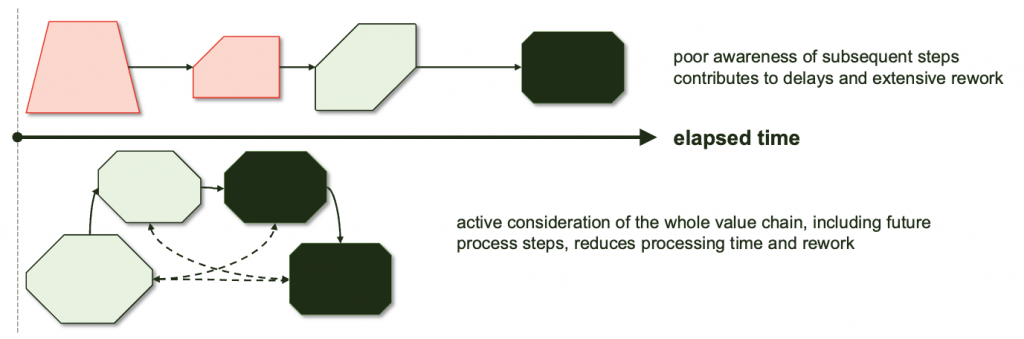

Even if the individual tasks in a long sequence are handled efficiently, the whole process can still be inefficient. Individual contributions are handled and reworked multiple times at different stages of the process, as earlier work is revised to correct elements that are not fit for purpose or do not fit together.

The extra time and effort to correct earlier work that was misdirected or disconnected from the goal tend to be concentrated at the end of the process, increasing demands on the people in the process who are most senior and most busy. This means that issues upstream, like variations in approach or gaps in coordination, can lead to lengthy delays downstream. When timelines are inflexible, lack of time for rework can compromise the quality of the final product.

When each worker understands their contribution in context, they know that there is still a lot of work to be done after they have done their bit. This requires some visibility of the whole process, and effective feedback loops so each contributor understands the relationship between what they do and what happens later. It also helps each worker to align their contributions to larger goals and flows of effort, improving the relevance and quality of their work.

When workers actively manage transitions in a process, as well as their individual inputs, they can reduce delays and handling time by coordinating their efforts with earlier and later steps. Each individual’s work can be considered done not when they put something down, but when someone else has picked it up, made any necessary corrections, and started making their own contribution.

Most publicly funded work is a complex product of many interconnected contributions. Gains in individual efficiency from segmenting tasks into production lines are often outweighed by the systemic inefficiencies of processing delays, multiple handling, and rework. Collaborative work can be more efficient when each contributor is aware of, and interacts with, other steps in the process, reducing total processing time through better coordination of both inputs and handovers.

Workers need a sense of the total process and goal to work in ways that are fit for purpose and fit together without major rework downstream. Quality improves at each step, including the final step. Effort is distributed across the value chain, instead of being concentrated at the end. Especially when the stakes are high, understanding the whole spectrum of doneness enables work to be both fast and well done.

social cohesion vs diversity