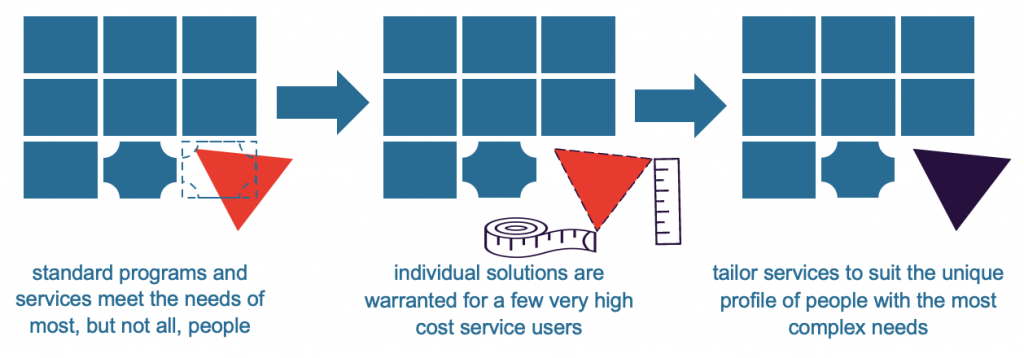

Standardised public programs and services are a bit like ‘off the rack’ clothing, which meets the needs of most people at relatively low cost, while higher cost targeted programs offer smaller batches of clothing for people who need less common sizes. But some people have needs so distinctive that, even when they consume many standardised and even targeted programs and services, often at considerable cost, none are fit for purpose.

Standardising the programs and services offered by publicly funded organisations is an efficient way to meet the needs of the majority of the population most of the time. Consistent services are not only cheaper per user, but are also easier to deliver with equitable access and quality at scale.

Publicly funded organisations are increasingly called upon to offer highly customised services for local, or even individual, users. Truly bespoke services are rare, however, because custom services tend to be very costly, variable quality, and difficult to administer.

People with intensive needs also tend to access targeted services from many different providers, each of which has separate management and accountability frameworks that can be hard to coordinate.

For a small proportion of citizens with particularly complex and distinctive needs, the typical mix of standardised and targeted publicly funded programs and services can be almost entirely unsuitable.

People may access many imperfectly targeted services over time, often at very high total cost, without ever having critical needs met.

Various mainstream and targeted services are managed separately, across different organisations and policy domains, so the scale and cost of failing to meet the needs of this small cohort may be invisible. Cases where the cost of delivering ineffective services is so high that a tailored, even individualised, service that could be more efficient as well as more effective are often not recognised, or the pathway is unclear.

Redesigning all mainstream and targeted public services to wrap around each individual citizen would be impractical and wildly inefficient. But making individuals the unit of analysis could help to identify citizens for whom genuinely bespoke public services could make sense. While it would be costly and unnecessary for nurses to call every citizen regularly to check how they’re feeling and offer proactive care, it could make sense for someone who would otherwise call an ambulance several times a month.

Recognising people who access many high-cost services across the system without having their needs met makes it possible to consider alternatives, like diverting those individuals into genuinely bespoke service responses designed around their needs.

Like mass-produced clothing, the mix of standard and targeted public programs and services have been good for most people who get a pretty good fit at relatively low cost. But a few people have nothing that fits their needs, no matter how many outfits they try. By working together to identify people with distinctive, unmet needs, publicly funded organisations can then consider the costs and benefits of tailoring bespoke solutions to meet those needs.

The higher unit costs of made-to-measure services, designed by experts to fit a single individual, may be offset by savings in the many ineffective services they no longer access. For some people, tailored solutions can be better and more cost-effective than supplying many mass-produced outfits, none of which fit.