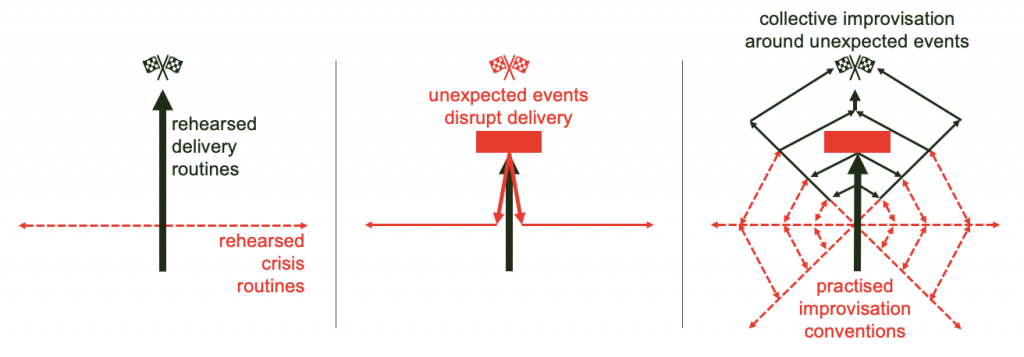

Planning responses to an uncertain future can be time and cost intensive, especially for complex organisations. Formalising routines for responding to predictable crisis events, like fire drills, helps publicly funded organisations to be efficient, consistent, and effective. But relying too much on predefined routines leaves organisations and teams without the ability to improvise, so when something really unexpected happens it can stop the whole show.

Publicly funded organisations tend to prioritise formal processes over the ability to improvise, particularly those in relatively safe and stable contexts. For an organisation with few crises and fewer competitors, it is worth investing in well-rehearsed routines.

Under pressure to maximise public value for taxpayer dollars, publicly funded organisations also strive for low overheads and efficient processing at scale. That pressure encourages lean workflows that minimise variation and immediately deploy any spare capacity.

A desire for consistency and reliability also tends to reinforce rehearsing formal routines to mitigate known risks. This shows in many different routine processes, from fire and evacuation drills to escalating novel questions to executives and waiting for direction.

It is prudent to plan for known unknowns, but building up growing numbers of prescribed responses to identified risks makes organisations, and society at large, more complicated. The more complex the system, the more parts and interactions can go wrong.

Restricting workers to defined routines deprives those workers of opportunities to develop creative problem-solving skills. As more routine work is automated, demand will grow for human skills like solving novel problems through collaborative improvisation.

When leaders fail to recognise and invest in collective improvisation as an organisational capability, workers often bear the consequences. It is unreasonable to expect that the resilience of individual workers will consistently offset the weakness of brittle systems.

Relying too much on formal routines, and even the resilience of motivated individuals, can be a barrier to collective problem-solving. Investing in the systemic capability to improvise collectively sets organisations up to respond to any crisis, expected or unexpected.

To respond collectively to unexpected events, workers need flexible frameworks and conventions to facilitate coordinated creativity. Boundaries and patterns for improvisation help to coordinate work in extraordinary times, until ‘normal’ conditions are restored.

Practising conventions for collective improvisation embeds resilience as a systemic capability. Just as jazz musicians practice musical conventions so they can improvise together, workers can practice problem-solving conventions to overcome barriers together.

Establishing protocols to mitigate every identified risk imposes many layers of rigid processes. Organisations with robust improvisational capability can have fewer, more flexible, processes that reduce complexity and increase adaptability. The more opportunities teams have to rehearse improvisational conventions, the better prepared they are for the increasing pace of change and automation of routine work.

Building and practising organisational conventions for collective improvisation is a systemic response to systemic challenges. This reduces unfair demands on the resilience of individual workers to mitigate risks.

Publicly funded organisations are too important for an unscripted event to be a show-stopper. By rehearsing conventions for collective improvisation they can adapt collaboratively when the show must go on.

social cohesion vs diversity