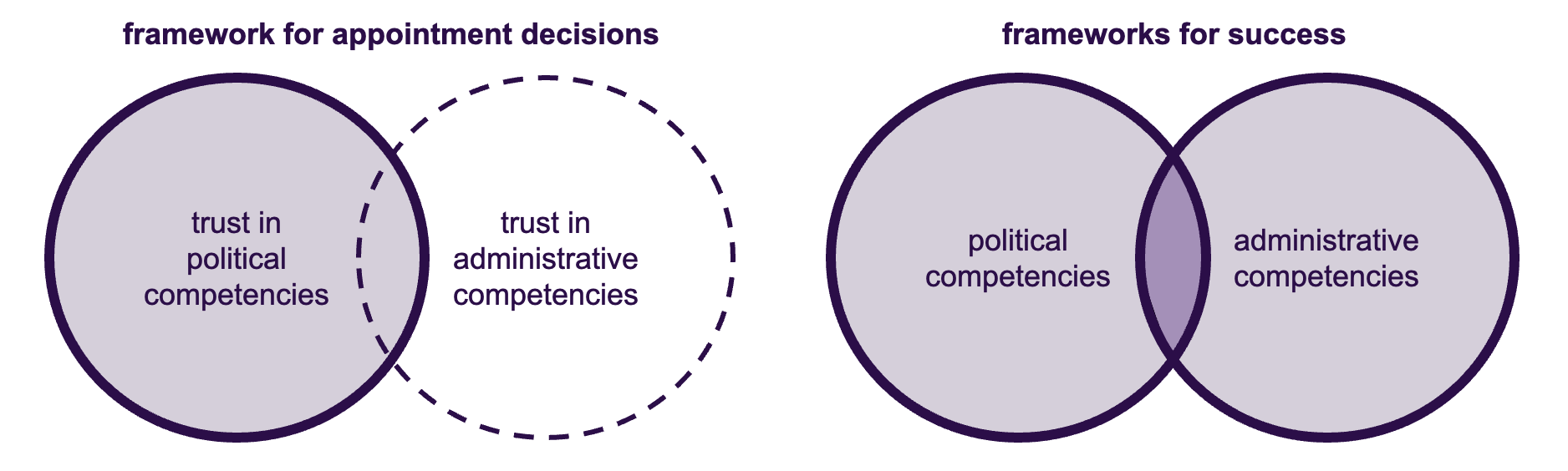

Ministers are typically responsible for, or at least influential in, appointments to senior publicly funded positions, like agency heads. For senior roles, successful appointees need to be competent administratively and politically. Politicians tend to be skilled at assessing political competency, putting their trust in candidates who share their vocabulary and move in similar circles. But decisions made with one eye closed can lead to misplaced trust.

Trust between political appointees and the people they appoint is an important and legitimate consideration. The stakes are high, and highly public, and good working relationships rely on mutual understanding.

Appointments made by politicians naturally recognise and respond to frameworks required for success in the political sphere. But few politicians have direct experience of public administration, so they tend to be less likely to recognise, or be confident assessing, the administrative capabilities of candidates.

A candidate with good political instincts, and networks that align with the Minister’s agenda, is likely to be rated highly by a political decision maker. So, it is understandable for trust in political competencies to be their default framework for appointment decisions.

But there is an important separation of duties between politicians and administrators. Westminster systems of government rely on partnerships to mobilise separate political and administrative competencies.

Partners with overlapping competencies are likely to have a good relationship, but may not be a great team. Engaging leaders with fantastic political skills may not be suited to managing technical, formal, and legally constrained work, even though cautious administrators may find it harder to connect with political partners.

Publicly funded organisations also need models of administrative competencies like impartiality, respect for the limits of legislative and delegated authority, transparency, and adherence to safeguards. If not, those values may be eroded, along with public trust.

Capability assessments that recognise and value both political and administrative competencies can help to inform recruitment decisions based on what matters most for success in a role, rather than what is easiest for decision makers to judge for themselves.

Formal induction and onboarding can help appointees, especially external hires, to build competencies that are not already strengths. Formal mentoring and support networks can be an ongoing source of advice to help leaders develop and apply the broad range of competencies required for success, and to understand the complex environment of public administration.

Open recruitment processes and transparent hiring decisions can also encourage fair decisions based on merit, assessed against all relevant competencies.

Decision makers who recognise that successful partnerships demand trust in a candidate’s administrative skills, as well as their political skills, are more likely to achieve effective partnerships and public policy goals. Transparent recruitment processes and decision criteria for senior roles can help to inform appointments based on competence in both the administrative and political spheres.

Robust assessments against all relevant capabilities can identify any areas of relative weakness up front. Then, formal induction, onboarding, mentoring, and support can help to address those gaps quickly.

Successful appointments come from a thorough assessment of all the capabilities that really matter, and not just judgements about who we trust.