Unlike the private sector, where most goods and services are sold or traded in real time, most public revenue is collected from citizens in advance through mandatory systems like taxation. Publicly funded organisations often encourage workers to ‘work hard’ or ‘work smart’ to provide positive returns on public investment. Neither of these two approaches in isolation maximises return on investment or the interests of shareholders: the public.

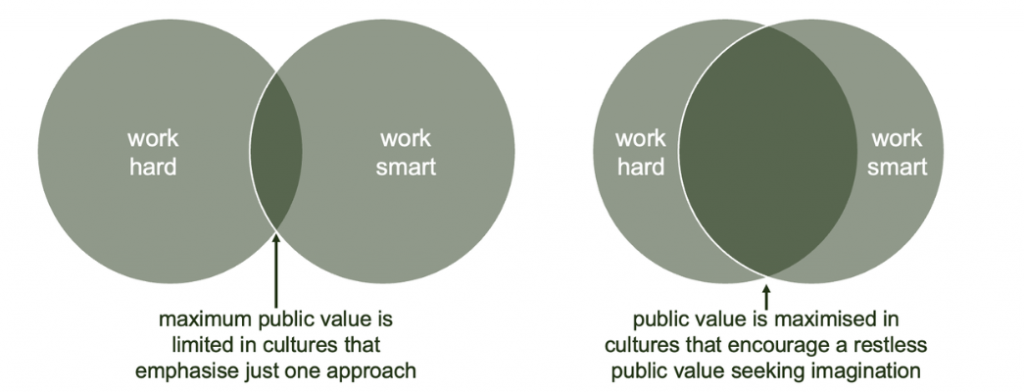

The cultures of publicly funded organisations tend to emphasise one of two broad approaches to using scarce public funds efficiently. Some cultures value working hard, where individuals work intensively to maximise the effort they contribute each day, with minimal energy diverted to indirect activities like coordination and monitoring. Other cultures value working smart, with greater emphasis on long-run efficiency at scale, including through investments in better coordination, processes, and automation.

Individual attitudes about work are shaped and reinforced by organisational cultures, often unconsciously. Most organisations formally and informally reward behaviours that align with the culture and discourage behaviours that are misaligned.

Cultural norms that emphasise working longer and harder can give the impression of high productivity while masking inefficiencies that limit overall output. Organisations with a ‘work hard’ culture can also be exhausting and frustrating for workers who feel pressured to put more and more effort into processes that are inefficient or duplicative.

Cultural norms that emphasise working smart can inadvertently encourage workers to stop working when their allocated tasks are complete, wasting capacity that could be used to create just a little more public value. Organisations with a ‘work smart’ culture can also be slow to deliver public value and respond to new challenges, or overinvest in process and administrative overheads.

Public value is not only a function of input quantity, like worker time and effort. It is also not only a function of efficiency, like the ratio of inputs to outputs over the long run. Public value is maximised by balancing both approaches, optimising the input rate and the rate of outputs per unit of input. This implies a culture of restless, public value seeking imaginations that strive to sustain high individual inputs and recognise opportunities to improve overall output and outcomes.

Leaders should reinforce the underlying objective of maximising public value, rewarding workers whose behaviour and results are consistent with that goal. Workers and teams who feel ownership of the outcomes of their work and not just their individual inputs, are likely to work both hard and smart.

When most of an organisation’s revenue is collected indirectly, compulsorily, and in advance, it can be difficult for workers to know whether they are delivering fair value for that investment. A culture geared towards maximising outcomes, rather than inputs, or outputs per unit of input, encourages people to work both hard and smart. Workers who understand the value of their work tend to be more motivated to work hard, while actively seeking out opportunities to increase the overall efficiency and effectiveness of their organisation or team.

The core obligation of publicly funded organisations and their workers is to maximise returns on public investment in their operations. That means delivering fair value for every public dollar invested, plus a little extra for the public interest on payment in advance.

social cohesion vs diversity