Cognitive biases affect people’s decisions, including how we assess and manage risk, so many organisations mandate structured risk management processes to counteract those biases. Unfortunately, compliance-oriented technical approaches to risk management can exacerbate the problem by creating dense registers and matrices that give an illusion of control which can, perversely, make us less likely to recognise and respond to risks.

Managing risk is such an important part of managing organisations and activities that formal standards like ISO 31000 have been defined to provide principles and guidelines for identifying, analysing, evaluating, treating, and monitoring risk. Formal standards prompt people to estimate likelihood and consequence and apply weighted equations to classify individual risks and to assess, and sometimes cost, aggregate risk.

Highly structured risk management processes have been adopted widely, even where specific risk management techniques are not mandated, such as in listed corporations and publicly funded organisations. Complex methods prompted organisations to create risk management teams to administer the process, often under the oversight of board-level committees.

Even if technical risk management processes are followed diligently, they rely on subjective judgements at each step. As each risk is identified, analysed, and evaluated, we accumulate rather than eliminate cognitive biases. The illusion of mathematical precision does not correct for underlying biases; it just creates a comforting, albeit false, sense of security.

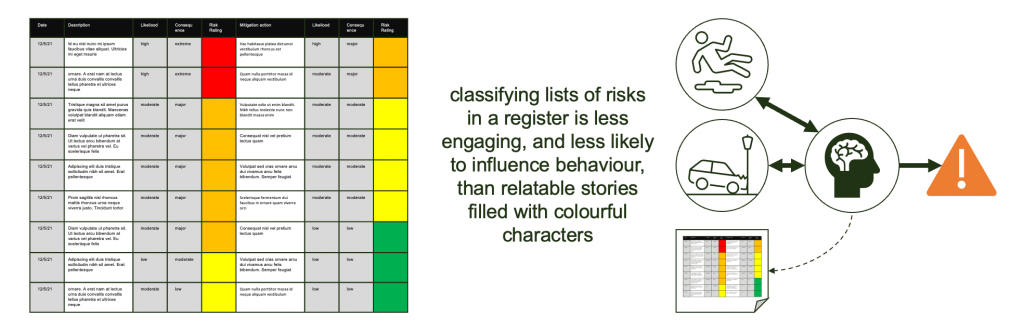

Large, complex risk registers are difficult to interpret, let alone retain to inform day-to-day activities, so even the most comprehensive risk register seldom helps people to accurately integrate risk probabilities into their decisions. The two activities are often entirely separate: we obediently add risks to registers when directed, then continue to make decisions based on the biases and heuristics we keep in our heads.

Risk management is only effective if it influences our behaviour in ways that deliver better outcomes, but human behaviour is not easy to change with statistics. Data about lifestyle risks is not enough to make most people choose to smoke less or exercise more and risky drivers are not deterred by car accident statistics.

Analysing lists of risks has value, but a relatable story is more likely to change behaviour than a high risk rating. Real world stories and illustrative vignettes can raise awareness of risks and appropriate mitigations. High risk workplaces, for example, might schedule ‘safety moments’ where workers share their own risk and safety stories. Diverting a percentage of the effort expended on technical risk management to focus on behaviour could dramatically improve outcomes.

It is easy for structured, technical, and often boring risk management processes to give us false confidence that risks are being analysed comprehensively and appropriate controls applied, so we can focus on something else. But to manage risk actively, managers and workers need stories and habits that help them stay alert to risks every day, not just when the risk management team asks them to update the register.

Cognitive biases make it hard for us to recognise and respond appropriately to risks, but complicated risk management tools are not good at influencing action. The act of packing and sorting risks into lifeless registers can make us less likely to register a risk when it arises in the real world, so risk management processes become just one more risk to manage.

social cohesion vs diversity