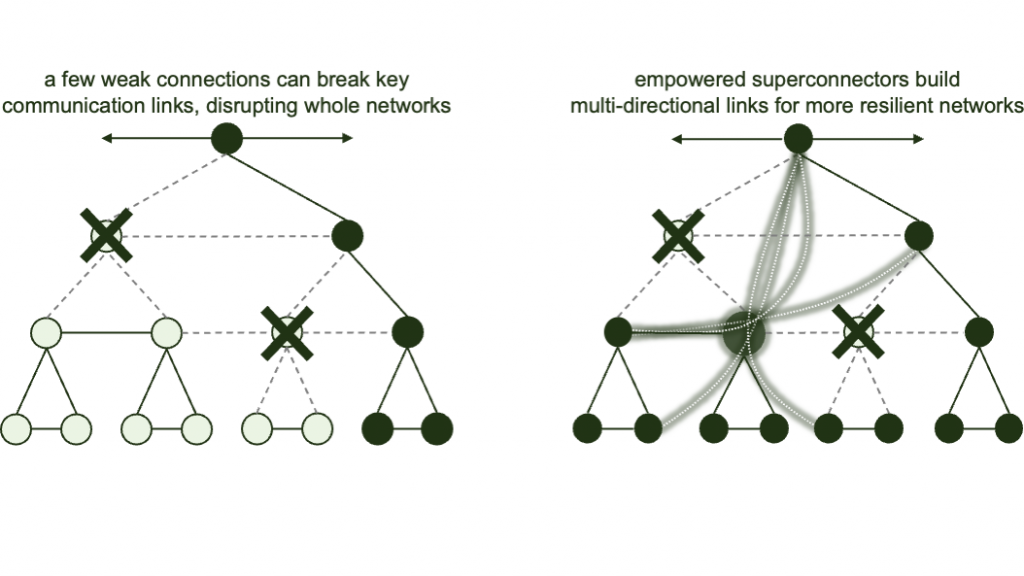

Connections and collaboration tend to be driven from the top in many publicly funded organisations, by executives and managers who allocate and link work across units. If people in these key roles are not great networkers, then the whole system can suffer from poor coordination, duplication, and missed opportunities to share perspectives, techniques, and skills. A weak connection at the top can cut the power to, and from, whole teams of workers.

Publicly funded organisations are often large and complex, so it is impossible to know everyone and everything that is going on. With so much activity involving so many people, ensuring effective collaboration requires substantial time, effort, and investment in collaborative tools and processes.

Service delivery roles tend to be busy and focused on connecting with customers rather than colleagues, and large organisations often rely on hierarchies to direct and control work by breaking it into manageable chunks and allocating those chunks to individuals.

Not every manager is a great collaborator. Some prefer working independently, or have come to their current role from a different professional background.

If an organisation relies too heavily on managerial links between teams, then the whole organisation can suffer when an individual manager is not a good conductor for the flow of information. Even otherwise skilled managers can disempower workers by blocking the flow of information and collaboration, making their teams feel undervalued and marginalised.

Communication flows that follow rigid pathways tend to promote silo cultures, diminishing opportunities for collaboration across the network. A persistent failure to collaborate has real costs. Output is reduced due to duplication and poor coordination of effort, and the quality of work declines because complementary skills are not mobilised and workers are disengaged from each other and, increasingly, from the organisation.

Some people are highly skilled networkers and collaborators who engage easily and efficiently with colleagues to build links across teams. These superconnectors are excellent information conduits, regardless of whether they are in managerial roles.

Building on the strengths of natural superconnectors, wherever they sit in an organisation, creates efficient, strong, resilient networks that can reduce any damage done by other, weaker connections.

Organisations can maximise the value of superconnectors by recognising their special skills and giving them an expansive remit to share information in many directions, strengthening the organisation by routing information through the strongest links.

Harnessing the power of superconnectors based on their skills, rather than their position in the hierarchy, enriches and strengthens organisational networks. Mobilising the strengths of superior networkers also tends to be more efficient than lifting the networking skills of a manager who lacks their natural aptitude.

Superconnectors can bridge structural gaps to boost productivity by reducing duplication and improving coordination. They can also unlock better solutions by mobilising broader insights and skills, and improve morale by strengthening organisational culture.

Empowering superconnectors recognises the work they are often already doing to connect dots, and harnesses that work to power up the organisation.

social cohesion vs diversity