The way policy proposals are communicated can affect whether decision makers and stakeholders accept or reject a policy. Policy experts tend to be good at gathering and interpreting evidence to inform policy proposals, but often struggle to make a compelling case for their proposals to people who are not experts. Even the most carefully collated facts and recommendations rarely tell a persuasive story for decision makers and the public.

Policy workers are trained to provide evidence to inform decisions. The harder the evidence, the more persuasive it is for expert audiences, so proposals tend to present concise facts and summary analysis.

The ability to tell an engaging and persuasive story is rarely seen as a core skill for policy specialists. Explaining a policy and its effects is often delegated or outsourced to communications specialists only after the big decisions have been made.

This model developed when decision makers relied heavily on the advice of professional policy workers. Now, despite rhetoric about evidence-based policy making, decision makers use information from many sources, including traditional and social media, lobbyists, political advisers, and partisan think tanks.

Policy expertise lacks the perceived authority that it once enjoyed, and a recommendation based on expert technical analysis is not automatically persuasive to decision makers or the public. The market for advice is contested and cold facts wrapped in technical jargon struggle to gain attention or support from audiences of non-experts.

Most participants in the market for policy ideas have an agenda and strive to make their ideas engaging and persuasive. Traditional and social media prefer stories that are engaging and contentious to attract readers. Lobbyists, think tanks, and political advisers have political aims and alliances. Powerful stories can be both appealing and misleading, encouraging decision makers to implement policy ideas that seem attractive, even if the evidence is weak.

Most people are more interested in stories than lists of facts. They understand and relate to narratives and recognisable characters much more readily than dense summaries of evidence. Policy experts can help their advice to be heard and understood by enriching evidence-based proposals with accessible stories.

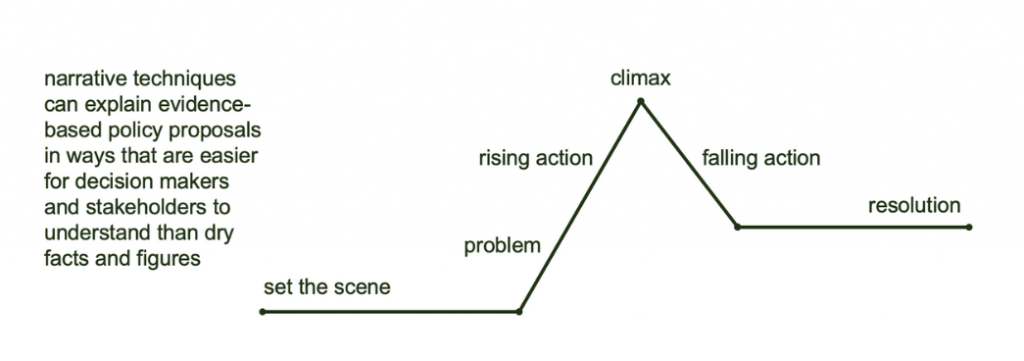

Narrative structures can quickly establish context and characters for an engaging policy story, like a change to environmental protections that will improve public health but impose new costs on some businesses. Using stories to explain the problem builds tension and demand for action, in the form of the proposed policy change. Costs of a proposed change are challenges to that action, which will be overcome in the climax. Finally, the resolution of the narrative demonstrates how the future will be better because of the proposal.

People are persuaded by information when they perceive it, attend to it, and understand it. Storytelling is a useful framework for attracting attention and conveying meaning. By identifying with the characters in a story, decision makers find it easier to understand the issues and implications of a proposal. Design policy informed by robust analysis, but explain policy with relatable stories.

Expressing evidence, proposed actions, and consequences in a narrative format helps experts to compete with other persuasive actors and avoid overwhelming audiences with technical jargon. People can make informed decisions only when they really understand a policy proposal, who will be affected, and how society will benefit. Good public policy, well told, is more likely to end with a happily ever after.

social cohesion vs diversity