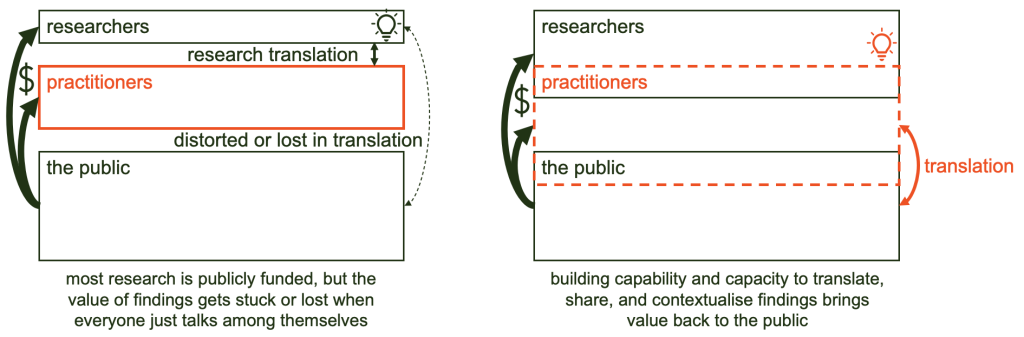

Public funds are a major driver of academic research, but it takes a long time for the benefits of most research to trickle down, if it ever does. Academics are mostly engaged in speaking to each other, often in ways that exclude practitioners and the public. Non-academics who find and communicate findings often do so selectively because they have something to sell. When everyone just talks among themselves, a lot of value is lost in translation.

Research agendas are driven and framed by the interests of researchers, which may or may not align with the public interest. Similarly, the public rarely engages in debates within the research community.

The barriers to entry are high. Researchers can only share their detailed, highly technical knowledge with people who have similar knowledge. They generally work to advance the knowledge of experts, rather than to bring practitioners, or the public, along with them.

Practitioners in publicly funded organisations are often busy providing services, rather than mining research papers for new insights. They also communicate more readily among themselves than with researchers, or to distil and translate insights into advice for members of the public.

Publicly funded research is expected, ultimately, to benefit the public, but the pathway to realising that value is often unclear, long, and treacherous. It can take decades for insights from research to filter into public awareness, if ever.

Even if practitioners or members of the public want to engage with research findings, technical language and high levels of assumed knowledge make academic sources difficult to interpret. Information also tends to be hidden behind paywalls for the public, but readily accessible from within research institutions.

People who do communicate research findings to practitioners and the public often do so with an agenda. Advice from people with news or products to sell is often selective, unreliable, and out of context.

The need to speed up the transfer of knowledge from research to practice is well understood, and the field of research translation has emerged to address it. We need a similar process, and focus on translation, to bring information and insights to the public.

Public funders could impose a condition of funding that researchers publish findings not only behind paywalls for other academics, but also summaries for the public. While few academics are likely to produce genuinely plain English summaries, their efforts are likely to benefit practitioners and interested lay-people.

Publicly funded practitioners can extend those benefits to the broader public. They need a clear role, and the skills, to interrogate, translate, communicate, and contextualise findings in accessible ways.

Research funded by the public should return value to the public in the form of better lives, services, and knowledge about the world. But, so far, waiting for insight to trickle down has been slow and unreliable.

Requiring researchers to publish summaries that are accessible to non-academic audiences will help practitioners and the public to find and apply research insights. It will also help them to critically assess claims from people who have something to sell.

Practitioners also have an important role mediating between researchers and the public. We need to build skills and expectations that publicly funded organisations will transfer value back to the public by contextualising, sharing, and translating research findings in ways that everyone can understand.

social cohesion vs diversity