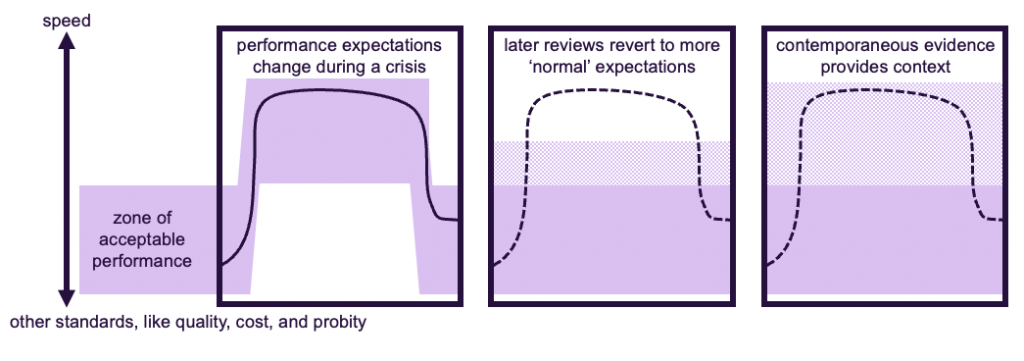

Publicly funded organisations are expected to meet high standards for minimising costs, maximising quality and equity, and ensuring probity. This takes time, which is usually an accepted trade-off until expectations shift in a crisis and speed becomes the most important factor. Decisions made in a crisis are often not assessed until later, when normal expectations resume, exposing decision makers to blame for failing business-as-usual standards.

Important checks and balances attach to spending public money for the public good. Publicly funded organisations must ensure high standards of probity, equity, fairness, and accountability, which means they often move more slowly than the private sector.

During a crisis, this measured pace is no longer acceptable, as the authorising environment for public decision makers shifts to demand faster responses. Decision makers, under pressure to just ‘get it done’, have less time to gather relevant facts, and less time for robust processes to protect probity, fairness, and accountability.

During a crisis, stakeholders generally accept that normal standards of performance are relaxed, or even set aside, to expedite an urgent response.

After a crisis has passed, normal expectations are quickly reasserted, and imperfect decisions made in the heat of the moment may be subject to a formal enquiry later. At their best, formal reviews can improve preparations for future crises, but many degenerate into assigning blame for unintended consequences. Too often, reviewers retrospectively apply business as usual expectations to abnormal crisis situations. Departures from standard practice in standard times are judged with the benefit of hindsight.

The context of the crisis—ambiguity, urgency, and fear—are easily forgotten once the moment has passed. It can be hard for decision makers to recall and justify when and why decisions were made, and what information was available to them at the time.

Contemporaneous records rarely seem like a priority in the moment, but are essential to inform later reflection and protect decision makers who act in good faith. Processes to record decisions as events unfold, noting the context and reasons, need not be onerous. A light touch process can reduce gaps in evidence or loss of context without slowing the crisis response.

Simple strategies can be effective, such as assigning an ‘evidence officer’ to accompany key decision makers and record decisions, context, and supporting information, or copying an ‘evidence mailbox’ on decisions communicated by email. Strategies to create contemporaneous records are easy to use, relatively inexpensive, and minimise distraction and delays for busy decision makers.

When a crisis shifts the range of acceptable performance to prioritise speed over everything else, the pressure to act fast is immense. Decision makers who cannot respond quickly are judged harshly in the moment, but decision makers to act in good faith in the moment are often judged harshly in retrospect, when held accountable to business-as-usual standards like efficiency, probity, quality, and equity.

Contemporaneous records of decisions made in a crisis, and the evidence available at the time, help to improve the acuity of hindsight by explaining those decisions in context. Even if subsequent investigators cannot independently recall the heat of the moment, decision makers can explain trade-offs and departures from the normal rules of engagement, raising the standards of reviews, as well as crisis responses.