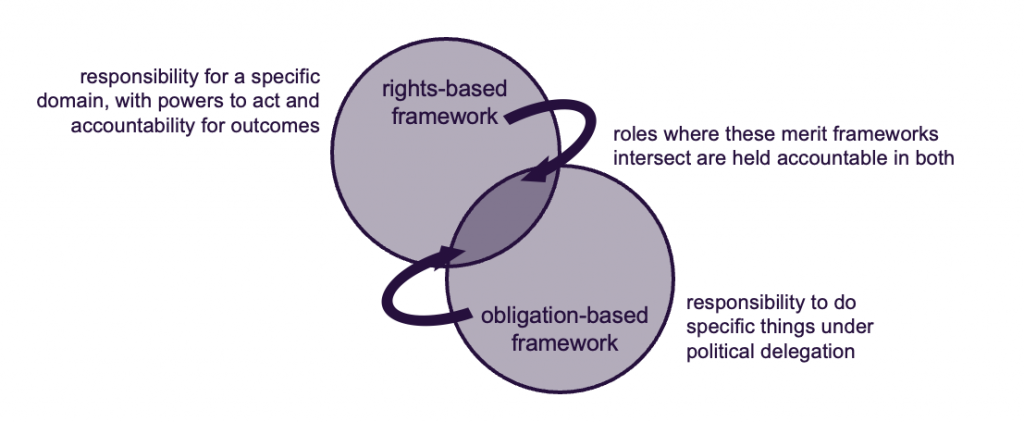

People expect public appointments to be based on merit, but different merits matter for different roles. Most appointments in publicly funded organisations use obligation-based frameworks, emphasising the responsibility to do specific things. But leaders who rise through the ranks under this framework are also accountable in the rights-based framework for political appointments, emphasising ministerial responsibility for decisions within a domain.

Democracies demand policy leadership from local representatives who are elected based on political merit. Representatives with ministerial powers for specific purposes, like health or education, are often not experts, but are held accountable for outcomes. Citizens also demand administrative competence from publicly funded organisations staffed by people with relevant skills, expertise, and experience, who are appointed through transparent processes.

These contrasting expectations imply different frameworks for assessing merit. Both are legitimate for roles that are clearly political, or clearly administrative, but confusing for leadership roles with characteristics of both. Being open to the best talent from both frameworks maximises the chances of finding great leaders.

Appointments to leadership roles in publicly funded organisations are often made, or at least influenced, by political decision-makers. These decisions are often made through a rights-based framework that values the confidence and trust of the responsible minister.

People appointed through this framework may lack some capabilities valued by an obligations-based framework, like operational credibility and experience. Similarly, people appointed through an obligations-based framework may lack some capabilities that are highly valued by political decision-makers.

The success of an executive, or the organisation they lead, can be undermined by relative weakness in the merits from either framework. Failures can erode both short-term public value and long-term public trust.

Great leaders of publicly funded organisations can be appointed legitimately under either framework, but rarely arrive with the full set of capabilities from both.

Regardless of which merit framework is relatively stronger for any individual executive, they will need support to understand and fulfil all the responsibilities imposed from both. This can include onboarding that emphasises features of the organisation or authorising environment that are unfamiliar, support teams with merits that balance the executive’s weaknesses, and access to formal and informal mentoring and advice.

An executive is not an individual contributor, but the figurehead and focal point for a team. Balancing capabilities within the team across both frameworks sets the executive and the team up for success.

It is rare for leaders of publicly funded organisations to enter complex roles with perfectly balanced merits across two very different frameworks, so they always need some systemic support to help them succeed.

Setting up systems to rapidly improve, or balance, executive capability gaps means that organisations can support leaders from diverse backgrounds. This enlarges the talent pool of potential leaders, while reducing the risk that they, or the organisations they lead, will fail to deliver on core responsibilities.

Regardless of which set of merits a leader has when they enter an executive role, they will be judged on the terms of both frameworks. For them to succeed, everyone needs to understand both what a publicly funded executive is responsible to do, and for whom.