There are almost always competing views about how public resources should be used to address a specific public policy need. Sometimes those different views arise from very different frames of reference, based on entirely different types of evidence and analysis. Making decisions that reconcile those differences, informed by valuable insights from multiple perspectives, is not as simple as weighing up each side’s arguments on the same scale.

People approaching public policy problems from different directions can, and often do, disagree about the sources of evidence that are most relevant, useful, or even legitimate. The individuals and groups who are directly affected by an issue tend to see the facts quite differently from policy or academic specialists, who tend to value different types of evidence.

Ways of knowing and solving problems within a community are often richly contextual, based on shared experience of specific issues in a specific place. Powerful stories, easily dismissed as anecdotes by analysts and experts, are often more accessible and persuasive to local people than peer-reviewed studies and large datasets. Evidence from complex analysis and dense research, by contrast, can appear irrelevant, absurdly abstract, and even heartless.

When the different parties to an issue are weighing different evidence, using different scales, it is almost inevitable that they will come to different conclusions. If fundamental differences in how people understand a problem are not addressed, or even acknowledged, they can contribute to tension and mistrust between communities and experts. This makes workable solutions harder to find, and even harder to implement.

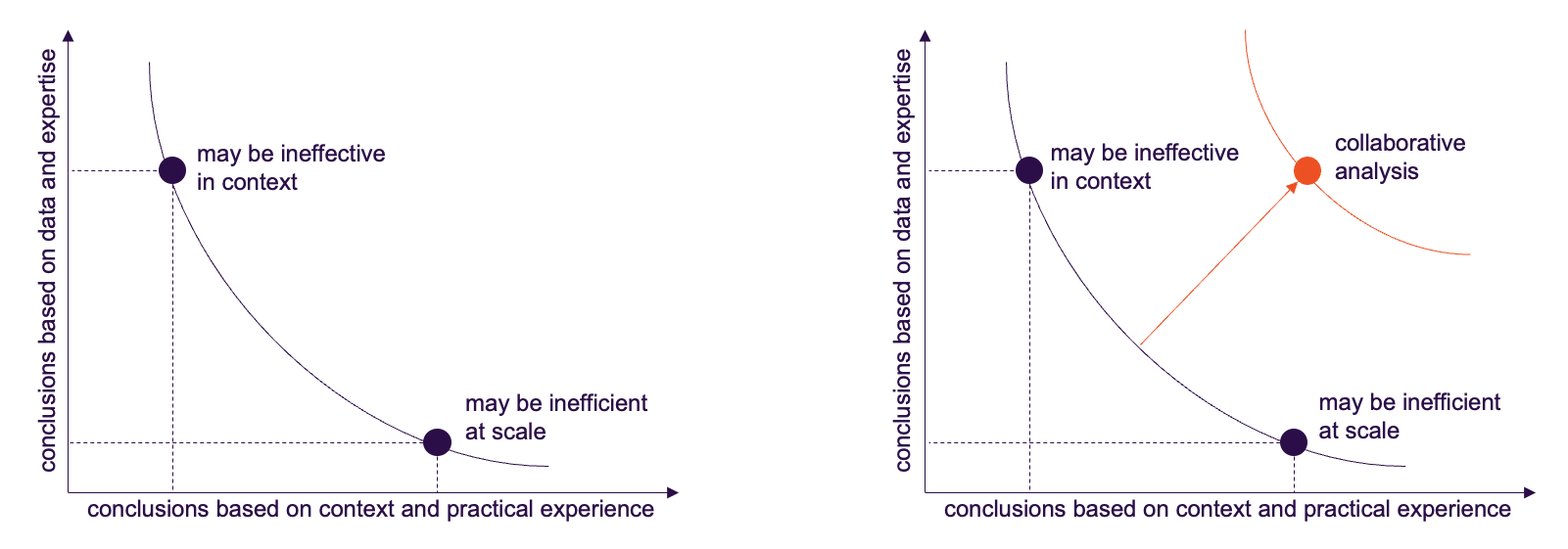

Trying to balance wildly different points of view can lead to ineffective action that satisfies nobody. Without the inclination, access, or skills to consider broader evidence or implications, communities often form expectations that would be unrealistic at scale. Relying solely on adaptation and analysis of robust evidence can miss critical contextual cues that undermine implementation of theoretically sound policy decisions.

Genuinely collaborative analysis requires more than just listening politely without really understanding. To find common ground, people first need enough common language to recognise and name it.

An independent facilitator mediating between perspectives can help to set ground rules and support participants to build trust and collaborate in good faith to find better solutions. People affected by a policy issue can invite experts and decision makers into their point of view, helping outsiders to understand local experiences and insights. People who can interpret complex data and evidence can explain why it is important and what it means for this problem in this community by teaching local people enough about the topic and the data to really understand that evidence.

Collaborative analysis takes time and effort to shift the conversation from competition between incompatible frameworks to synthesis of different perspectives. An independent facilitator can help to create an equal speech space, fostering trust and resisting efforts by any party to tip the scales in their favour.

Local issues are rarely purely local or purely systemic. Designing wholly bespoke solutions to every problem in every place is inefficient, but imposing standardised solutions everywhere is often ineffective. Collaborative analysis gives everyone access to a shared set of facts and a shared scale with which to weigh them. By drawing together the insights of all parties, the balance of decision-making can shift from the weight of authority or argument to the weight of evidence.