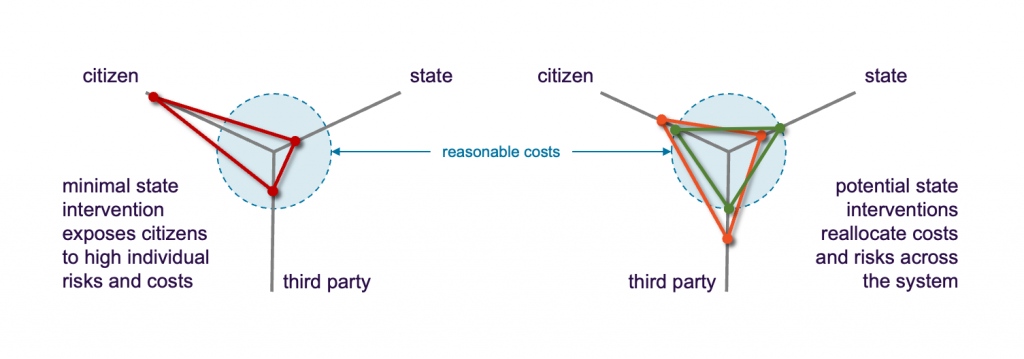

States insure citizens against the risk of harms by providing services or imposing obligations that reduce or transfer costs and improve outcomes. They may intervene in systems directly or compel citizens or third parties to act to reduce risks. There can be practical reasons to impose social welfare obligations on third parties, like an employer or supplier, but outcomes are just as unfair if they are compulsorily charged social insurance premiums.

Solutions to social problems are often complex, with high administrative, financial, and economic costs that affect many parties directly or indirectly. It can be difficult to understand how the costs and benefits of a policy intervention, or the underlying social problem it is trying to solve, are shared between individual citizens, the state, and third parties like employers, manufacturers, or service providers.

States try to meet social needs efficiently, effectively, and equitably. Sometimes it is more appropriate, and efficient, for states to intervene by providing services or other forms of support directly. In other cases, the most efficient overall solution can be administered by a third party, like employers who are well placed to calculate and facilitate income-related payments like superannuation and income taxes.

When the state imposes obligations on some parties for the benefit of society, those costs may be unfair to the affected parties. The substantial costs of administering social welfare obligations also tend to be less transparent than direct taxation, hiding the true costs of state intervention.

Third party administration of social interventions limits access to people who have a relationship with the provider. Systems where healthcare or domestic violence leave are linked to employment, for example, exclude people who do not have jobs.

Third party providers may be inefficient or ineffective. Employers may misuse workers’ health information, for example, and using domestic violence leave does not connect people in need with appropriate services.

Fair, efficient, and effective policy responses need to be designed for the whole system, based on analysis of costs and benefits for all affected parties. Analysing the financial and administrative costs and risks for each party helps identity which option best balances the mix of obligations to optimise efficiency, effectiveness, and equity across the system.

It can be attractive to impose obligations on third parties if the total cost will be lower for them than for individual citizens or the state. But even the most efficient model is not a good investment if the outcomes are ineffective or inequitable. If the ‘best’ policy response imposes an undue burden on a third party, then they should be compensated, transferring financial costs to a more appropriate funding source.

To design fair, efficient, and effective public policy, we need to analyse and balance the costs and benefits of all the different options for all affected parties, not just compare the total costs and benefits of each option.

What looks like an efficient solution may need tweaks to be fair and effective. If some people will fall through the cracks of third party administration, for example, then supplementary supports may be needed, which might make a state-led model more efficient overall.

Similarly, if efficient system responses impose undue costs on a third party, then those costs should be compensated and made transparent to the public. Imposing social costs on a third party can look like a cost saving, but not if they end up paying premium prices for a poor system response.