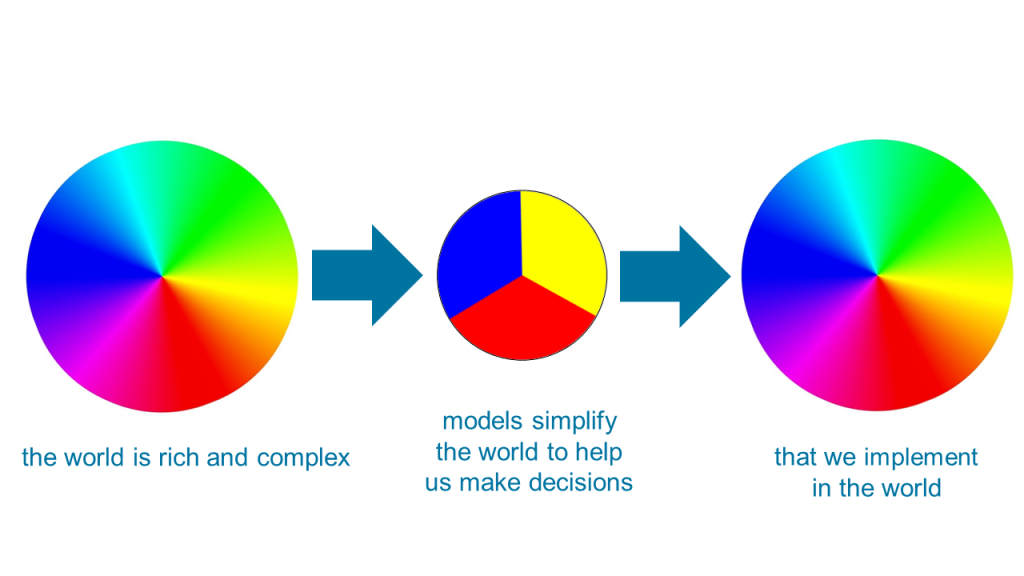

The real world is complex, so people in publicly funded organisations often use models to filter through complexity for the details that are most relevant to key decisions. Models can inform policy decisions by predicting outcomes based on historical data and assumptions about selected details. Models can also simplify policy problems too much, unintentionally obscuring important truths and blinding us to the colour and complexity of the real world.

Real world policy problems are complicated and often messy. Human brains can easily be overwhelmed by high stakes decisions with apparently infinite variables. Policy workers often use simplifying models to help by removing or ignoring unnecessary complexity, retaining only the features that are critical to inform decisions. Models filter and transform selected data to present summary information that makes the costs and benefits of policy decisions easier to see.

Models are built on choices about which features of reality are essential and which can be ignored, as well as assumptions about how the world will respond to various actions. Good choices and assumptions can produce robust models and valid predictions, informing good policy decisions that address complex problems.

By presenting a simplified world, a model can falsely imply that it has also simplified the problem. It can be seductive for policy workers to admire the elegance of a modelled solution through rose-coloured glasses, ignoring or underestimating its limitations, and fall into circular arguments that describe solutions with reference to the model instead of to the world.

Gaps or weak assumptions in a model can easily become blind spots in policy decisions. Solutions may fit the model perfectly but not fit the real world. An insurance-based model for social welfare support, for example, may incorrectly assume that support needs are stable and easily costed, and that tactics such as loss adjustment and delaying claims will improve financial sustainability of the scheme.

A model is a means to an end, not an end in itself. Models can be useful tools, but only if used as intended. Models should be challenged before they are trusted, including by reframing questions and varying key assumptions to see if results are still clear. Different models, focused on different features of a problem, can help to test different perspectives.

Bring fresh eyes, with real-world perspectives into the process at regular intervals to sense-check both assumptions and results, and to identify any important missing elements. This can also help to recognise and address real world expectations, such as that welfare support will be timely, recognise variation, and be fair, rather than being distorted by the skills and biases of individual assessors, the sophistication of the customer, or the business practices of insurers.

People in publicly funded organisations need models and decision support tools to help them manage complexity, but even the most beautiful, elegant, and powerful models can never capture the colour and complexity of real life.

Using a range of different lenses to challenge models, assumptions, and outputs at multiple stages in the modelling process can reveal blind spots early, before we rely on a model to support high stakes decisions.

When we understand the strengths, and the limitations, of our models, we can be more confident that they are illuminating effective solutions rather than merely obscuring detail. We must take care to describe the world, not the model, or risk losing touch with reality, like Narcissus, gazing at the beauty of an imperfect reflection.