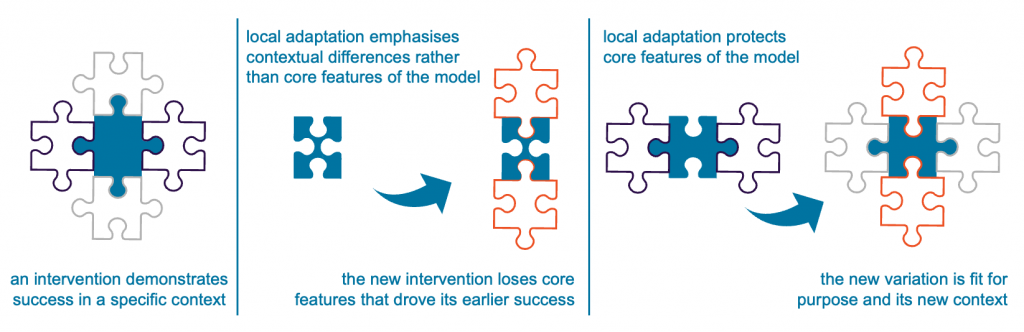

Policy workers often seek to adopt interventions that have proven effective elsewhere to solve local problems. Since no two policy contexts are identical, it is common to adapt imported interventions to fit local circumstances. Without a clear understanding of which features of an intervention make it worthwhile, and which can be readily adapted, changes intended to make interventions a better fit can end up making them not fit for purpose.

Policy workers responding to local challenges often investigate and draw on interventions that have demonstrated success solving similar problems elsewhere. Importing, or building on, an intervention with an existing evidence base can reduce costs and speed up implementation, reducing the need for costly local research and trials to demonstrate value.

Engaging local stakeholders in codesign to adapt a proven intervention encourages adoption and better outcomes by tailoring the model to local conditions.

Evidence supporting an initiative—even if it has been formally evaluated—is not always clear about which features drive its effectiveness. Similarly, it is not always clear what is a feature of the intervention, and what is a feature of local implementation.

Changing evidence-based interventions for the local context can easily undermine their effectiveness. Too many changes, or even just one tweak to a core driver of benefits, can fundamentally alter the intervention.

Even if core features of the intervention are retained, variations in implementation can lead to unpredictable results. Different training, motivation, experience, or time to adapt to a new intervention can shift a new approach into something very like past practice.

Key attractions of importing an evidence-based intervention include accelerating implementation and reducing costs and risks. Tinkering with interventions or implementation approaches can result in variations that are effectively new and unproven interventions, subject to all the usual delays, costs, and risks.

Local adaptation and codesign processes for importing evidence-based interventions are often beneficial, but they need to protect the core features that made the intervention effective elsewhere. Adapting at the margins, while preserving fidelity at the core, requires thorough understanding of the evidence, the intervention, and how it was implemented.

Published studies rarely include enough detail to adopt an intervention, but guidance from experienced practitioners can help to differentiate the features that matter, like vaccine storage temperatures or the COVID-19 protein spike targeted by many vaccines. Cosmetic features, like the colour of the vaccine liquid or the type of health professional trained to deliver vaccines, can be readily adjusted to local conditions.

Importing an evidence-based model from another context almost always requires some degree of adaptation to the intervention and the implementation approach. Complex solutions need to be translated rather than merely transplanted to new contexts. But that process of adaptation needs to be grounded in a robust understanding of what made the intervention effective elsewhere and what can be adjusted to local needs without undermining expected outcomes.

Expert advice from practitioners can help plug gaps in the literature so that codesign avoids compromising the integrity of core intervention and implementation features. Preserving features that underpin evidence of success helps to ensure that local adaptations are both fit for the conditions and fit for purpose.