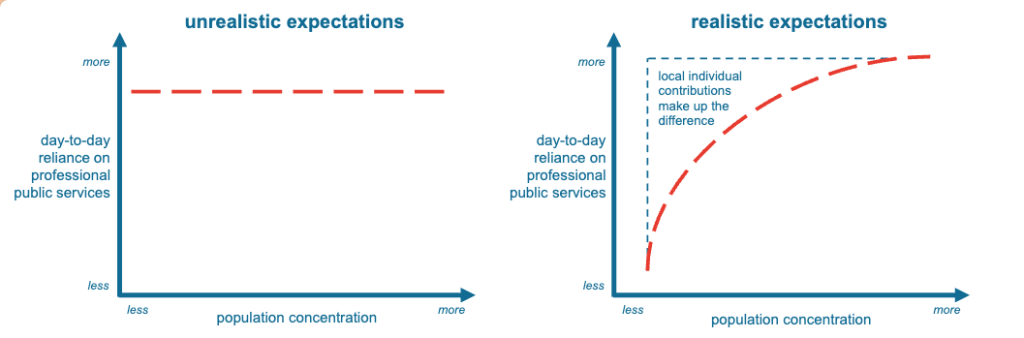

Individuals contribute both resources and effort to maintaining a safe society, fulfilling their end of a social contract with the state. Goals have much in common across different communities, but expectations of what, when, and how individuals and states contribute will vary with the local context and environment. When there is a large gap between individual and state contributions, communities with great expectations can fall short of meeting them.

Maintaining equivalent public services regardless of context or population concentration is inefficient and often impractical. Municipal water and full-time fire fighters make sense in dense urban centres, but not in every rural and remote community with far fewer people, and far more flammable vegetation.

How, and how much, individuals contribute to their communities tend to differ accordingly. People in dense urban areas tend to contribute more financial resources in the form of taxation, levies, and rates, while more remote counterparts tend to contribute more direct effort, perhaps as volunteer fire fighters. People living in rural areas expect, and are expected, to contribute more direct skills and labour, and to rely less on publicly funded services in everyday life.

When the balance of obligations between individuals and governments is unclear, we can end up with mismatched expectations between community members and publicly funded organisations. This can cause tension between people and services, and between community members who have different expectations, and so make different contributions.

Expectations of professional public services have risen over time, and populations have become more urban. Tree-changers and younger people who expect more public services may volunteer less to support their communities. This also limits the reserves of trained and experienced volunteers who can help professional responders in a real crisis, and lower engagement in organised local networks can weaken resilience.

The obligations of individuals to communities vary for many reasons, some practical and some preference. One of those obligations is setting and reinforcing shared local expectations about the balance of professional public services and local effort.

A strong community identity and commitment to helping your neighbours matter more in communities with less immediate access to professional public services. That means services need to work differently with strong local communities, supporting the capacity of local volunteers to help themselves, and ensuring that professional help coordinates with local networks when it is really needed. That includes joint training and material support for local volunteers, as well as appropriate minimum regulations and standards.

Tensions arise when the expectations of individuals, communities, and publicly funded organisations are unclear or mismatched. More mobile, and more urbanised, populations mean that communities need to invest more, and more sustained, effort in setting and reinforcing shared, and realistic, expectations.

Motivated and coordinated communities can support safe, comfortable, and rewarding lives with far less day-to-day reliance on professional public services than is typical in dense population centres. That takes effort from community members to organise, and from public services to build capacity and coordinate with local networks, especially in a crisis. A healthy social fabric weaves together the individual, the collective, and the institutional to achieve great expectations, with no gaps and no shadow of parting.