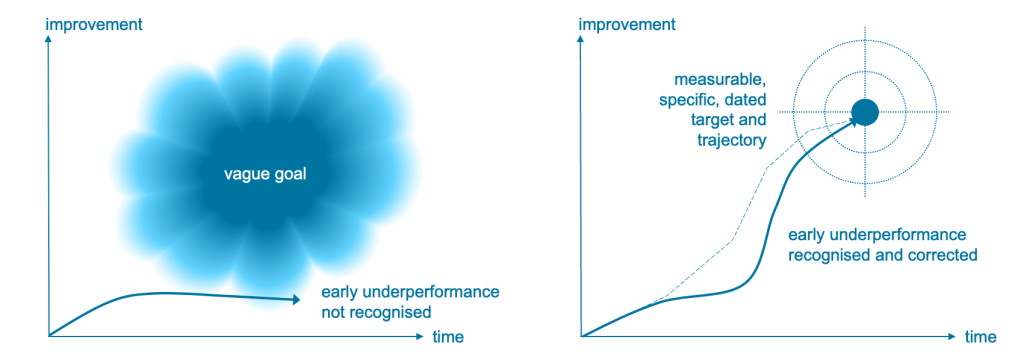

People working in publicly funded organisations tend to have clear views about how they want to make the world a better place, but often find it difficult to describe exactly what they plan to change, and by how much, within a given timeframe. Vague goals make it easy for people to lie to themselves about their progress and trajectory over time. It is also harder and more costly for others to verify the truth that lies beneath optimistic progress reports.

It is often easier to describe a vague change from the current state than to specify a target end state. For example, it is easier to commit to ‘improve outcomes’ than to set clear targets for exactly what will improve, by how much, and by when. Even if precise targets are considered, many people prefer the face-saving wiggle room of vague goals, just in case they fall short.

People also tend to talk more about big goals up front than they do during implementation. Early planning tends to be optimistic about outcomes, perhaps because the time, effort, and costs are still unclear.

Once a plan is agreed, people often feel accountable for delivering its actions, rather than its outcomes. They are much more comfortable committing to doing specific tasks than achieving specific targets.

Without clear targets, any improvement can be, and often is, presented as success. This can be misleading if the advance is very small, is exceeded by the costs, or is on an irrelevant or unimportant dimension.

Without a planned trajectory, it is easy for busy people to convince themselves, and others, that the work is on track. Outright fraud in progress reporting is rare, but self-serving bias is inevitable. It would take a lot of time and effort to independently verify objective progress towards a vague goal, so a veneer of activity reports often hides an emerging failure of outcomes.

Overstating progress obscures early signs of trouble that could prompt a change of approach for better outcomes. Pretending everything is fine now leads to disappointment later when the time or budget runs out.

It is far quicker, easier, and more accurate to monitor progress against plans that define specific targets and trajectories, rather than vague goals. For example, a goal to ‘improve results’ could be defined as a 2% increase per year for four years in a specific per capita measure, relative to a defined baseline.

Mapping specific, tangible, and unambiguous targets and milestones gives visibility of expected progress over time. Monitoring progress against expectations quickly highlights any slippage, giving an early warning that a change is needed to get things back on track.

Objective indicators also make it impossible for well-meaning people to kid themselves that lagging work is actually on track. It is also easier to independently verify progress reports, if necessary.

Tangible targets, trajectories, and milestones stop people from lying to themselves, and organisations, about their progress and likely success. Specifying how success will be measured and tracked from the outset ensures that any hint of improvement cannot be mistaken for, or misrepresented as, enough improvement. When early expectations are not being met, organisations can seize the opportunity to make adjustments that improve the likelihood of success.

Clear, well-specified and tangible targets, trajectories, and milestones that support an objective rather than subjective view of progress can be verified easily, but seldom need independent review. Delivery teams and decision makers who recognise true indicators of progress can respond with confidence rather than wondering what lies beneath rosy progress reports.